“She throws her head back and pushes her chest forward and lets go a huge blast right into the centre of his body. The rivulets and streams of red scarring run across his chest and up around his throat. She’d put her hand on his heart and stopped him dead.”

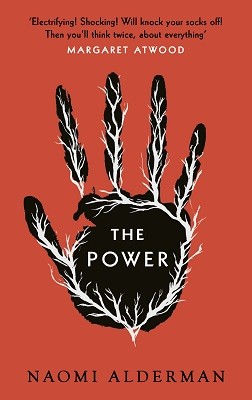

I’ve been putting off writing this review for a while because I’m still not 100% sure how I feel about it. Naomi Alderman’s novel The Power is both gripping and disturbing. As it goes on I both wanted desperately to look away while compulsively reading. Although much of it is empowering, ferocious, fascinating and thrilling, in parts it is visceral, devastating, painful and uncomfortable, and that’s exactly the point.

The winner of 2017’s Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, Alderman’s novel begins as young girls all over the world start discovering a power within them, something they’ve always had, a kind of twist in them that unleashes electric shocks. Suddenly, with a flick of their fingers, girls can inflict pain, pleasure, or death. They can awaken this power in older women, and now all baby girls are being born with this power in them, ready and waiting. Suddenly, the women have a powerful strength beyond a man’s reach.

The winner of 2017’s Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, Alderman’s novel begins as young girls all over the world start discovering a power within them, something they’ve always had, a kind of twist in them that unleashes electric shocks. Suddenly, with a flick of their fingers, girls can inflict pain, pleasure, or death. They can awaken this power in older women, and now all baby girls are being born with this power in them, ready and waiting. Suddenly, the women have a powerful strength beyond a man’s reach.

The men become afraid of women as gender roles gradually reverse. Boys are soon segregated into single sex schools for their own safety as riots spread over the world; the women are striking back. The shift is gradual but extreme; they become military weapons to harness their natural aggression, harsh dictators…over the years they turn on men, humiliating them and using them to satisfy their desires, sexual violence reversing as men become the victims of women. The power is fetishized, drugs made to enhance it, and men become more classically submissive as women take the matriarchal lead. Some men fear that women will wipe men out, use them for breeding and nothing else – a conspiracy theory which, in certain corners of the world, begin to come true.

Through all this a new, feminised religion starts up: “Jews: look to Miriam, not Moses … Muslims: look to Fatimah, not Muhammad. Buddhists: remember Tara, the mother of liberation. Christians: pray to Mary for your salvation.” Allie, an abused foster child, transforms herself into Mother Eve, and seeks to build a new world. Alderman creates vibrant characters to conduct the thought experiment at the heart of The Power; the religious leader, the crime boss, a female American politician, and Tunde, a male Nigerian journalist whose awe of the power slowly turns to fear as he is attacked, manipulated and powerless as an attractive young man in a woman’s world. Through these characters we see how the power changes the dynamics of the world, how the old patriarchal ways are slowly buried as the matriarchy makes the same mistakes – violence, sexual exploitation and subordination is turned onto men as Alderman forces us to witness an uncomfortable, mirrored image of society.

Alderman ingeniously structures the novel as a proposed piece of historical fiction from a frustrated male historian (Neil Adam Amon) who is asking advice from a female colleague (Naomi), who suggests he try publishing the novel under a woman’s name and immediately fetishizes the very notion of a patriarchal world. The male author is writing thousands of years in the future and dares to question the natural dominance of women over men and how it developed – to Naomi the world has always been just as it is, women with the power and men as their submissive counterparts. She glibly remarks that the world would be a gentler, peaceful place if it was run by men, due to their naturally calmer and paternal instincts. The novel counts through the years to a global cataclysm, where the world as we know it is destroyed and begun again.

Alderman has created a perceptive, astute and brilliantly written thought experiment which defied all my expectations. She forces us to look at our own gendered society, down to the smallest details of email tone. Women will recognise the patronising way they’re often treated at work, will perhaps recognise the fear of walking alone at night…its an uncomfortable reminder as well as an astoundingly clever piece of feminist, sci-fi literature which shows the flaws of both genders and us as human beings. By the end we’re forced to witness violent war crimes as female soldiers rape and kill male villagers – just because they can – in a deeply disturbing and visceral part of the novel which shows how far the powerful had fallen in just a decade. Despite the uncomfortable and violent nature of much of the book, it’s far from a depressing read. Complex, clever, and compulsively readable The Power is as intriguing as it is disturbing – disturbing only because it holds a mirror up to the society we live in.